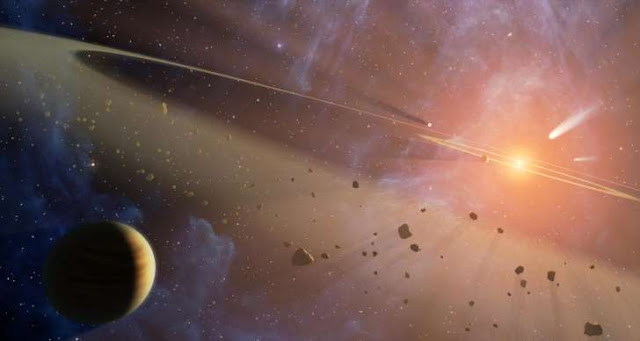

NASA has already found tons of exoplanets

around nearby stars, and will spot countless more once the James Webb

Space Telescope (JWST) launches. The problem is that scientists aren't

exactly sure which planet-star combinations are most likely to support

life. A new NASA study has found that planets orbiting small stars like Trappist-1

could retain their oceans for billions of years, even if they're quite

close -- provided the star emits just the right amount of infrared

radiation.

For the foreseeable future, astronomers will be scanning red dwarf stars for habitable planets, rather than other types like our sun. That's because they're easier to find and small enough that the wobble of small, Earth-like planets is detectable. On top of that, the amount of light dip is noticeable when a planet passes in front, and scientists can detect the composition of its atmosphere based on how much starlight it absorbs.

Because of that, scientists are obviously very concerned about which red dwarf stars and planets can support life. That's where the new study, done by a team from NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies and the Earth-Life Science Institute at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, comes in.

If a planet is too cold, any water will freeze into ice, making life formation challenging. If it's too hot, water will evaporate and rise up into the stratosphere, where it will get broken into hydrogen and oxygen by the star's UV (ultraviolet) light. The latter state, called a "moist greenhouse," eventually leads to the loss of all oceans, killing any chances for life.

For the foreseeable future, astronomers will be scanning red dwarf stars for habitable planets, rather than other types like our sun. That's because they're easier to find and small enough that the wobble of small, Earth-like planets is detectable. On top of that, the amount of light dip is noticeable when a planet passes in front, and scientists can detect the composition of its atmosphere based on how much starlight it absorbs.

Because of that, scientists are obviously very concerned about which red dwarf stars and planets can support life. That's where the new study, done by a team from NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies and the Earth-Life Science Institute at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, comes in.

If a planet is too cold, any water will freeze into ice, making life formation challenging. If it's too hot, water will evaporate and rise up into the stratosphere, where it will get broken into hydrogen and oxygen by the star's UV (ultraviolet) light. The latter state, called a "moist greenhouse," eventually leads to the loss of all oceans, killing any chances for life.

ConversionConversion EmoticonEmoticon